Water

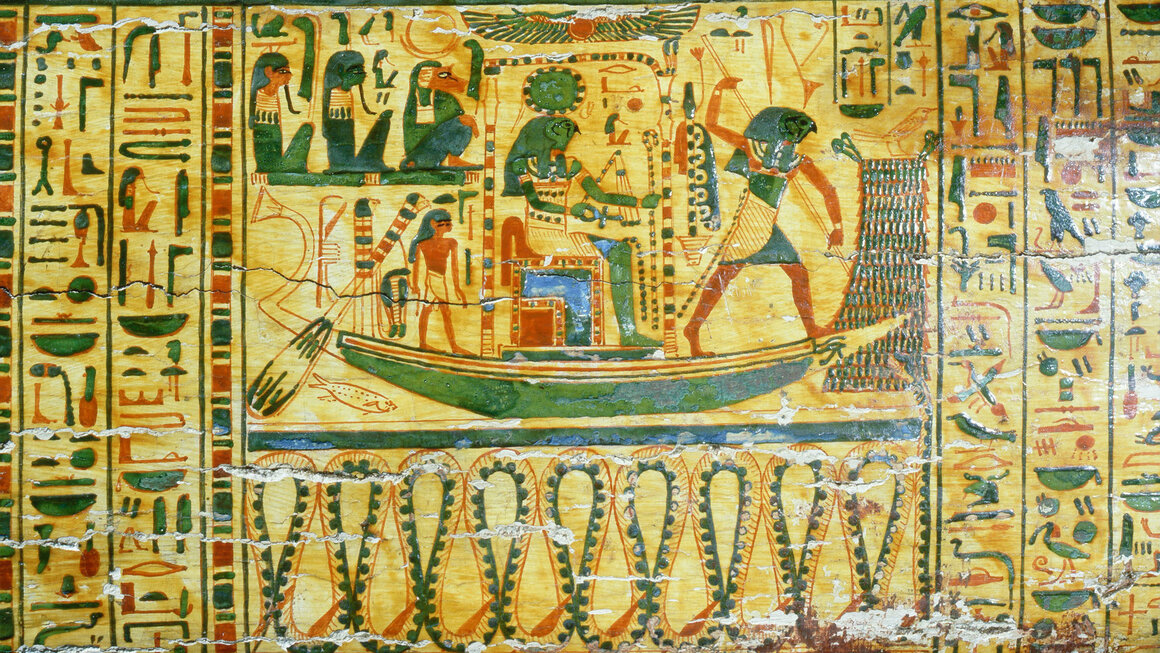

The ancient African fluvial environment had a profound impact on the African spiritual system, which in turn impacted back on African humanity by giving order, meaning, significance, and higher purpose to daily life. Nowhere is this more dramatic and obvious than in Kemet. It is here that the River Nile and an imaginary underground river, of which the Nile was undoubtedly the archetype, respectively ordered and regulated the life of the living and that of the Dead and, in fact, profoundly influenced all existence and all conceptions of existence.

The Nile is the longest and one of the most dominant rivers in the world. It runs for more than 4,000 miles from south to north through East Central and North East Africa, from its source in the region of the Great Lakes to its estuary on the Mediterranean; from the place of the beginnings of humans through to the places of the beginnings of civilization, in Kush, also called Ta-Seti, literally “Land of the Bow” or Nubia. People as well as progress also flowed northward, following this waterway along its valley from the heart of Africa. The Nile was the world’s first transcontinental cultural highway. But it was not only water, people, and their culture that this river has carried as it arose in the highlands of Africa and journeyed across varied terrain to empty itself into the Mediterranean. There is another gift. Fertile silt, eroded from upland, has always been transported in its yearly floods and deposited in places that would have been part of the largest desert in the world but for this annual replenishing nourishment from the longest river in the world.

The Nile has run through Africa and the lives of Africans for millennia. In Kemet, at first it brought devastating and fearful floods to vulnerable settlements that clung precariously along its banks to thin margins of land with agricultural possibilities. Then as human knowledge and skill developed, and predictability and flood control evolved, threat became promise, and the Nile flood a welcome deluge to provide for an increasingly more productive and secure future. Here the river provided water for irrigation, transportation, communication, drinking, washing, and sewage disposal. It also yielded large quantities of fish, birds, and other edible animals. That part of the Nile Valley had become a magnet that attracted more and more settlers from all directions. So was born the foremost country in the ancient world, owing much of its life to water in the form of the then foremost river in the world.

hargeisa, somaliland population 1,250,000

brazzaville, republic of congo population 2,200,000

havana, cuba population 3,000,000 port au prince, haiti population 800,000 kumasi, ghana population 1,600,000 lome, togo population 900,000

dar es salaam, tanzania population 3,500,000 matola, mozambique population 725,000 panama city, panama population 600,000

riyadh, saudi arabia population 9,000,000 gaborone, botswana population 300,000

mombasa, kenya population 900,000 kuala lumpur, malaysia population 2,000,000

kingston, jamaica population 1,500,000

luanda, angola population 4,000,000

phnom penh, cambodia population 2,500,000

addis ababa, ethiopia population 3,500,000

sanaa, yemen population 3,000,000

kinshasa, dr congo population 9,000,000

harare, zimbabwe population 2,500,000

shanghai, china population 22,000,000 cairo, egypt population 12,000,000

maracaibo, venezuela population 2,000,000 windhoek, namibia population 300,000

mexico city, mexico population 10,000,000 brikama, gambia population 85,000

nouakchott, mauritania population 750,000 kandahar, afghanistan population 600,000

khartoum, sudan population 3,000,000 kigali, rwanda population 850,000

ouagadougou, burkina faso population 2,000,000 quezon city, philippines population 4,000,000 bangui, central african republic population 620,000 n'djamena, chad population 850,000

anju, north korea population 400,000 libreville, gabon population 700,000

mumbai, india population 18,000,000 cape town, south africa population 4,500,000

georgetown, guyana population 300,000 sousse, tunisia population 250,000 lagos, nigeria population 10,000,000 ho chi minh, vietnam population 9,500,000 bata, equatorial guinea population 300,000 cotonou, benin population 900,000

dakar, senegal population 3,200,000 bafata, guinea bissau population 35,000 bamako, mali population 2,500,000 faisalabad, pakistan population 3,500,000

niamey, niger population 900,000 mogadishu, somalia population 3,000,000 bujumbura, burundi population 450,000 ndola, zambia population 450,000